The term Contribution Analysis was introduced by the late John Mayne 25 years ago when he wanted to motivate people involved in development programmes to look at their rationale and impact critically. It opened the field of impact evaluation to alternative methods, when econometric methodologies to assess net effects proved inappropriate. I first heard about contribution analysis at the 2009 European Evaluation Society conference in Prague when the evaluator Charles Lusthaus, who sat next to me, corrected the spelling of Mayne’s name in my notebook.

In a 2001 paper, Mayne developed a practical stepwise approach to theory-based evaluation. In short: make a good theory of change, identify key assumptions in this theory of change, and focus M&E and research on these key assumptions. The result of a contribution analysis is a nuanced, evidence-based narrative about how an intervention contributes to development outcomes.

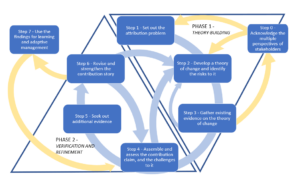

We developed the approach further in the Centre for Development Impact (CDI), a community of practice that started 10 years ago as partnership between the Institute of Development Studies, the consultancy firm Itad, and the University of East Anglia. Together with the participants in our courses – generally working in the context of international development in settings where multiple interventions are piloted and adapted at the same time – we now conceptualise the six-steps-process proposed by Mayne as a cycle of iterative refinement and learning around the theory of change of programme, and added two more steps that acknowledge different viewpoints (step 0) and highlight the importance of a user focus in the process and deliverables of an evaluation (step 7) – see Figure 1.

FIGURE 1 – Enhanced contribution analysis

Source: Adapted from Ton (2021)

Since 2009, contribution analysis has become a more familiar term in the evaluation community. This uptake coincided with the move in the evaluation field away from net-effect measurements alone, and towards the facilitation of learning for adaptive management of interventions through portfolio evaluations. The field experienced a broadening of methods accepted to make causal inferences about impact and opened the field to more explanatory, learning-oriented impact evaluations.

Evaluation practice, however, always needs several years to adapt to new trends, such as this broadening of methods in evaluation theory. Especially in university courses on international development and global studies, increasing computational power coupled with novel econometric techniques has shifted the locus of teaching for impact evaluation towards development economics, where the definition of rigour is still highly biased towards net-effect results measurement. Development economics largely follows the US evaluation tradition that defined impact evaluation as net-effect attribution to interventions, while the European tradition considered it more a study of the long-term and lasting effects of interventions. Due to this shift in paradigm in university schooling, many commissioners of impact evaluations still consider these econometric control/comparison group designs as the most rigorous way to implement impact evaluations. And, when these commissioners ask for these rigorous evaluation approaches, the evaluation practitioners will need to respond with proposals that do so. I argue that this focus on net-effects only implies lost learning opportunities.

This methodological tension around rigour in impact evaluations is still relevant. For example, in March 2024, I attended a meeting of VIDE, the Dutch version of UKES, where Jelmer Kamstra acknowledged that within the Dutch Evaluation Office (IOB) there is still tension between those who prefer an accountability-oriented evaluation approach that looks for evidence of intended results of programmes versus people that want to learn from interventions in order to support transformational social change. He acknowledged that during the evaluation of the ‘Dialogue and Dissent’ programme, most of the supported NGOs that implemented advocacy projects funded by the programme were aware of these paradigmatic differences within the IOB and, perhaps ‘to-be-sure’, prioritised the accountability element. As a result, most NGOs relied heavily on results-counting in their narrative reporting, such as the number of rules or laws changed by the advocacy coalition, or the number of publications made during the period. He said that he would have preferred much more detailed information about the actual process and challenges of advocacy and how advocacy strategies evolved over time and in response to changes in the context. This would have helped him in the design of a new phase and a refinement of the funding approach. The understanding of how change happened would have been more informative than the bookkeeping of intended outcomes defined at the start of the projects.

So, how can we advance? I think that the concept ‘impact evaluation’ continues to push all of us in the wrong direction – towards research that tries to attribute short-term outcomes to a particular intervention instead of understanding how the support generates synergy with ongoing activities of all stakeholders involved, and in view of longer-term social change. I think that the term ‘impact evaluation’ could easily be substituted in most terms of references with the concept ‘contribution analysis’. When commissioners would do so, this would enhance learning processes that better acknowledge the complexity of social change and the need for adaptive management in implementation. Just use the ‘find-and-replace’ option, and far more interesting terms of reference will result, both for the commissioners and the evaluators.

A shift from ‘impact evaluations’ to ‘contribution analyses’ would also open up space for better, more appropriate evaluation questions that can be answered with methodological designs that generate real-time information for adaptive management. In its ten years, CDI published a series of 25 practice papers that reported on pilot experiences with less conventional methods for evaluating impact. Not all these methods survived the test of time. However, several did and are still inspiring evaluators to design their evaluations, such as, natural experiments by Michael Loevinson in 2013, process tracing by Mel Punton and Katherine Welle in 2015, realist evaluation (Punton et al., 2020), participatory statistics by Pauline Oosterhoff and Danny Burns in 2016, evaluability assessments by Richard Longhurst in 2016. However, it is increasingly evident that all these methods have limitations and validity threats when used in isolation. The mixing of methods is a craft; it requires being explicit about the limitations of methods, and it encourages people to compensate for these limitations by adding other methods – methods that may be inappropriate insolation but appropriate when being part of a mixed methods design. There is a need for evaluators who master this ‘craft of bricolage’ (Aston and Apgar, 2022): evaluators who intentionally and creatively combine elements of various methods to address evaluation challenges within real-world resource, time, and political constraints.

In the courses that we organize, contribution analysis is the overarching framework within which multiple methods are used, from the conventional ones to the more innovative ones. But always with a focus on what matters! For me, the key to evaluation design is step 4 in John Mayne’s iterative cycle (see Figure 1), where, after reviewing the information that is already available, the evaluators focus on the areas in the theory of change that are most likely to be challenged by a critical insider and/or sceptical outsider. The choice for these focal areas, which Marina Apgar and I call ‘causal hotspots’, helps to answer the questions that matter most and helps to increase the useability of the evaluation.

Learn how to design impact evaluations more effectively with “Contribution Analysis for Impact Evaluation” course convened by Giel Ton, Marina Apgar and Mieke Snijder. This course equips you with the tools to enhance impact evaluations by navigating complexities in development programs. Explore a structured approach to refining Theory of Change iteratively, alongside mixed-method research designs and innovative techniques like Qualitative Comparative Analysis and Realist Evaluation.