Every year, hundreds of millions of Muslims across the world pay a proportion – broadly 2,5% – of their wealth as zakat, one of the five pillars of Islam. On the occasion of Ramadan, when most zakat is paid, we highlight three preliminary findings emerging from a new nationally representative survey of 7,500 Sunni Pakistanis conducted in 2024. What they highlight is the immense magnitude and social importance of zakat – and the importance of better understanding its role in redistribution in Pakistan and beyond.

Zakat represents a significant channel through which redistribution and social protection works in practice, and yet, studies on how much is paid in zakat, to whom, and what its distributional impacts are, remain scarce. Most existing work is hypothetical—focusing on how much zakat could or should be paid—and has almost nothing to say about where its contributions actually go. Since 2021, a partnership between the International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD) and the Lahore University of Management Sciences has enabled a more systematic account of how zakat is paid in practice and how these dynamics shape social equity outcomes and state-society relationships.

1. Pakistanis are paying over 1.7 billion GBP in zakat every year

In a newly published factsheet, we estimate that self-identified Sunnis in Pakistan pay over 619 billion rupees (GBP 1.7 billion) in zakat annually. In 2024, the average zakat giver paid about 15,000 rupees (about GBP 43) with over 50 million Pakistanis contributing. Our data suggests that every year, more money is distributed to people in need in Pakistan through zakat than through the largest state-led cash transfer programme, the Benazir Income Support Programme (its budget for 2024/2025 is Rs 598.71billion). Similarly, more money is raised through zakat than through the federal excise duty (in 2023-2024 that was Rs 576 billion) and this amount exceeded what the country received in official development aid in 2022, despite it being among the largest aid recipients in South Asia. Needless to say, these are not substitutes – but they illustrate the importance of zakat in understanding redistribution in Pakistan. Remarkably, as we detail in the factsheet, this remains a conservative estimate, whereas the real amount is probably higher.

2. Pakistan’s State zakat fund is extremely unpopular

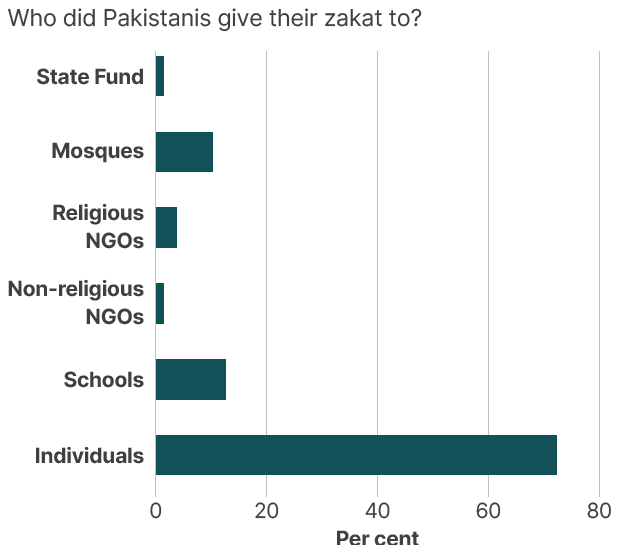

Who is all this zakat going to? Since the 1980s, Pakistan has had a system of compulsory collection of zakat, relying on a state-administered zakat fund and zakat councils at federal, provincial and district levels. However, most Pakistanis prefer to bypass the state fund—unsurprising in a context where individuals have low trust in the government. The national state fund collects only a fiftieth of what we estimate to be contributed annually, while survey respondents overwhelmingly noted that they prefer to manage their own zakat giving. In our survey, we find that less than 2% of zakat givers are going through the state fund.

Instead, as the graph below shows, the vast majority of zakat is disbursed directly to individuals. Some people prefer giving through intermediaries, but still want to avoid the state, giving instead to mosques and schools, and to a lesser extent, NGOs.

3. Most zakat payments are going to women

Does this preference for direct giving influence who receives zakat? While we are still conducting analysis to answer this question, one finding is undeniable: gender is a factor shaping zakat distribution. Through a conjoint survey experiment and the analysis of reported giving patterns, we consistently find that people significantly prefer giving zakat to women. This holds, regardless of whether the zakat giver is male or female.

Perhaps most notably, more than half of our respondents reported giving zakat exclusively to female recipients.

Women in Pakistan continue to face marginalisation and a range of barriers to participating in economic activity and accessing state social protection. Our findings imply that zakat givers are recognising these hardships, and considering them in their giving. Most notably, the profile most likely to be chosen in our conjoint experiment were widowed women, indicating a connection here between assessments of gender and economic vulnerability.

This is also not a trivial or necessarily expected result. While the Quran clearly identifies eligible categories of recipients — including the poor, the needy, those employed to administer zakat, those whose hearts are attracted to the faith, those in bondage or debt for God’s cause, and needy travellers—no specifications are outlined with respect to the gender of the recipient. But in practice, these things clearly interact.

Next steps: Research on the politics and practice of zakat giving in Pakistan

These findings highlight the need to think about non-state social protection and redistribution mechanisms in Muslim countries, particularly given the scale of zakat compared to other social protection channels. They also spark further questions: Who is more likely to give zakat? Why are people so unlikely to give to the state fund? Are there any other biases in giving dynamics—that is, are people more likely to give to people who live near them, or who share their same language or ethnic background? Are there regional differences in zakat dynamics or differences based on people’s religiosity or jurisprudential approach? What are the impacts of widespread zakat payment on people’s attitudes toward state-led redistribution, such as wealth taxes?

We are currently working on answering these questions. Interested readers should read our factsheet on zakat in Pakistan, and follow ICTD’s informality and tax research programme for more detailed results on the distributional impacts of zakat and its implications for wealth taxation in the coming months.