Biodiversity is back on the international policy agenda in a big way. The United Nations names biodiversity loss, alongside climate change and pollution, as part of an interlinked planetary ‘triple crisis’. The UK was instrumental in driving forward the 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which now guides national action plans on biodiversity all over the world.

The GBF’s targets bundle together wide-ranging concerns and approaches. These include a significant expansion of protected areas and ecological ‘restoration’ schemes, dramatic cuts to pollution and climate change impacts on biodiversity, the aim to strengthen governance capacity at all levels, and the aim to develop innovative financial schemes like green bonds and biodiversity offsets.

But in the rush for innovative, integrative and scalable solutions, caution is needed. Scepticism should be applied to claims about ostensibly cheap, top-down fixes and ‘win-win-win’ promises. We have witnessed decades of repeated failure to make meaningful progress on prior global biodiversity targets set under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Mainstream approaches and fundamental assumptions about cause and effect, and the relationships between society and nature, need to be rethought.

What’s being ignored?

UK and broader global action on biodiversity faces fundamental technical, social and ethical challenges at different scales. These are often hidden or side-lined in policy discussions. Yet they can have huge implications for policy coordination, conflict, and the wellbeing of people and the natural systems of which they are part.

In high level policy and media discourse, biodiversity is often discussed in a way that creates the impression of a singular, global problem and focus of action. This can communicate a sense of relevance to broaden engagement – but it can also create ambiguities at the policy level. The broad term ‘biodiversity’ can hide a plurality of ideas, concepts and phenomena.

Likewise, speaking of biodiversity as a global or planetary issue can emphasise broad patterns and the need for collective action. But aggregation and abstraction can also mask difference and variability across contexts. The dynamics of change, which may or may not involve habitat loss, are always specific to particular places where changes are actually occurring.

The result of these hidden assumptions is a high risk of policy fragmentation and mismatches between problems, prescribed actions and practice ‘on the ground’.

Ambiguities in policy

Biodiversity is a contested concept due to its multifaceted nature and the diverse ways it is understood and valued by different people and in different situations.

For example, scientists tend to frame biodiversity in more or less ‘eco-centric’ terms – as valuable in itself. In contrast, policymakers’ notions of biodiversity tend be human-centric, as a ‘stock’ of ‘resources’ which matters for its ability to satisfy human needs and desires. Policy action coming from this ‘anthropocentric’ position is increasingly justified in economic terms, framing biodiversity either as a provider of environmental ‘services’ to society (e.g. food security, climate resilience) or as a direct input to economic and financial growth.

Biodiversity frameworks try to reconcile these views and mediate ‘trade-offs’ between them. But this can create ambiguities, and these ambiguities matter. Both eco-centric and anthropocentric positions start from the idea that intensifying threat and loss of ‘variability among living organisms’ (as the CBD defines it) at a global scale is bad. But each is grounded in different ethical positions and points towards fundamentally different outcomes and ways to achieve them.

Ambiguity can gloss over or obscure the underlying politics of environmental change, affect the uptake of research evidence, and create fragmented or inconsistent knowledge and policy responses based on contradictory or overlapping but incommensurate approaches and ideas. This in turn can create technical hazards that cause problems for implementation, impede the effectiveness of conservation measures and threaten the integrity of ecosystems, species and livelihoods.

Who’s responsible?

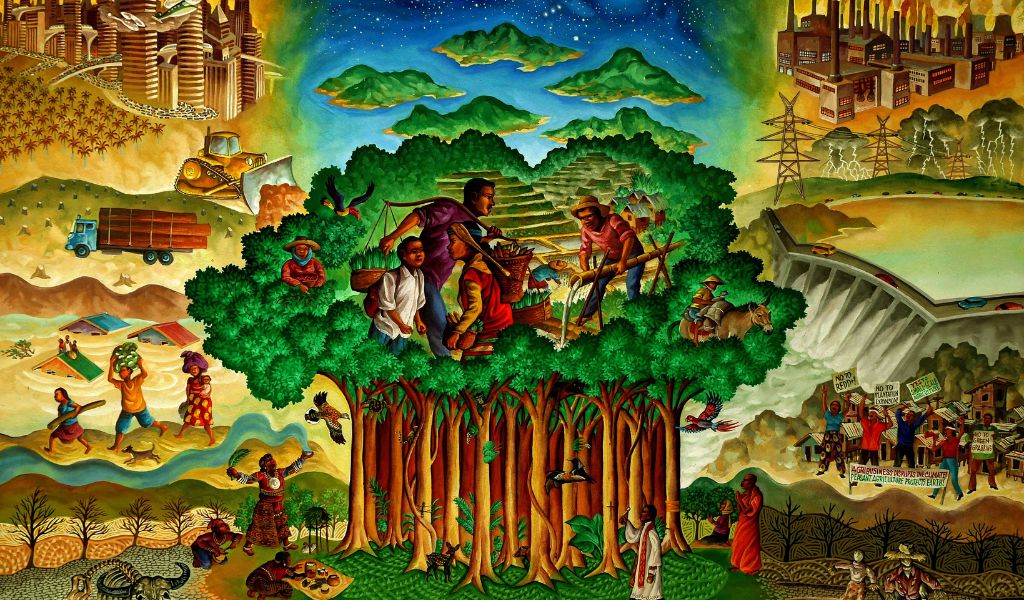

Problematically, the scope of what counts as ‘biodiversity’ in high level framings often privileges ideas about nature that leave people out of the picture. But healthy ecosystems are produced by interactions among people, non-humans and their environments. In many cases, people, across diverse cultures, have co-created the landscapes, ecosystems and habitats which conservation efforts are seeking to protect.

In contrast, people are placed back in the picture when it comes to assigning blame. Mainstream policy and media narratives claim that urgent global action is necessary to end humanity’s ‘war on nature’ and to reverse the damage that a growing human population ( a classic neo-Malthusian ‘red herring’) has done to life on Earth.

Drivers may indeed be caused by humans, but the story that blames ‘humanity’ as a whole is misleading. It flattens inequalities and implies that ‘we’re all in this together’. It exercises a politics that neglects systemic factors in processes of harmful environmental change, and shifts the blame away from those most responsible and who benefit the most.

The high level story may be powerful, but it leaves out the diversity of values people ascribe to their relationships with the more-than-human world. It ignores the sorts of emergent and ‘unmanaged’ biodiversity that can be created and flourish through human activities. These might be in agroecological settings that grow food and create habitat for wildlife, in cultivated forests, or diversity found in landraces – distinct, locally adapted domesticated varieties of plants and animals common in small-scale agricultural systems around the world.

The fact is, the main drivers of biodiversity loss at a global scale are related to processes of industrial extractivism, driven by unequal consumption, which in turn is justified by the imperative to sustain global economic growth. Yet the international community disproportionately focuses on rural landscapes in resource-rich countries of the Global South. Many biodiversity conservation and ecological restoration projects are established in places where resident populations have often already experienced histories of exclusion and political marginalisation.

Wilderness and fortress

Mainstream ideas about protecting biodiversity, including participatory and co-management paradigms, continue to be implicitly shaped to varying degrees by the classist, racist and colonialist notions of ‘pristine nature’ or ‘wilderness’.

Their underlying assumption is that people, especially poor people, are irrational and destructive and need to be separated from nature for it to thrive. This is reflected in resurgent discourses of ‘fortress conservation’, strict protectionism and ‘Half Earth’ that have had a strong influence on global spatial protection commitments like the so-called ‘30×30’ plan and Target 3 of the GBF.

Some biodiversity conservation strategies in rich Global North countries such as the UK aim to conserve ‘cultural landscapes’, many of which were created from past enclosure, rather than producing food more locally. In the process, the burden of feeding Britain gets shifted to other countries like Kenya, where intensive practices cause pollution and deplete soils, causing ecological harm and insecurities.

In this situation, markets reward capitalised businesses while creating landlessness and erasing commons. Resource use for export commodities compromises local and regional food security and socio-ecological well-being.

Pathways forward

Conservation projects can achieve locally positive outcomes, especially when they are responsive to place-based contextual social-ecological relationships and dynamics, are guided by situated knowledge of environmental change, and foreground considerations of justice.

But the truth is that, despite decades of target setting and global coordination, mainstream approaches have failed to slow ecological degradation and habitat loss on a global scale and can do more harm than good. Even the best-intended conservation projects can never address or neutralise the ultimate systemic drivers of global biodiversity loss.

Global calls to action and high-level agreements will continue to fail if we do not treat biodiversity loss as foremost a social and political problem. The search for consensus can create ambiguities in high level policy that create major challenges. Ignoring these ambiguities won’t work: instead, acknowledging them can foster productive dissensus, invite reflection on difference, complexity, plurality, and power relations, and so open up clearer pathways for policy and action.

Read: Why policy makers need to stop treating climate change in isolation

New priorities for humanitarian assistance, livelihoods and resilience