How products such as food and clothes are produced and brought to consumers – a set of activities known as value chains – is critical to reducing poverty and hunger, creating jobs and ensuring decent work, innovation and economic growth. If the ambitions of the Sustainable Development Goals are to be met, local, national and global value chains must be sustainable and inclusive. However, Covid-19 has further exposed and exacerbated the inequalities and weaknesses that exist within these chains. Food supplies in Africa and fast fashion globally are just two examples of why urgent action is required to ensure these value chains are made fairer and more resilient.

Winners and losers from globalised value chains

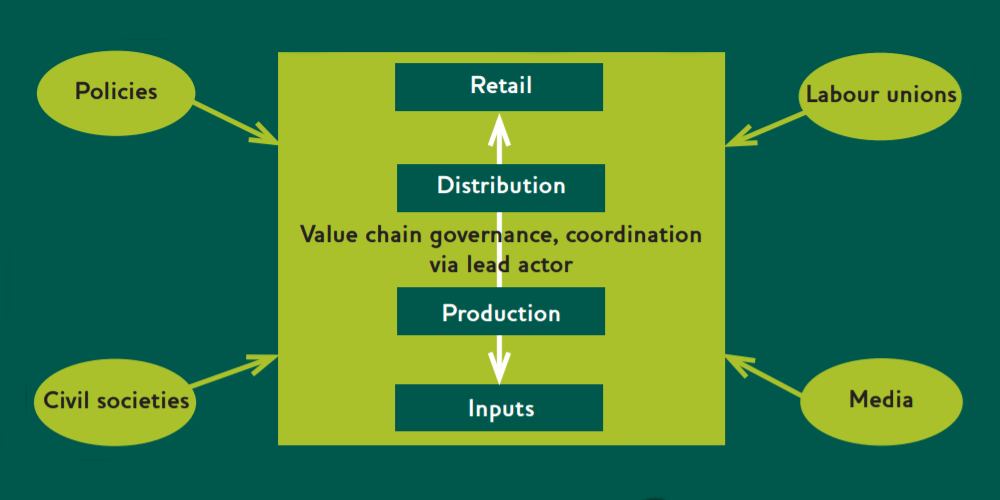

Value chains operate and interact across local, national and global levels. Global value chains have been central to the world economic system for over 30 years, and they account for around 50 per cent of all trade.

Research in the last two decades has shed light on the winners and losers from expanding global value chains. The multi-national corporations that dominate international trade face fierce competition on their home turf, mostly in high-income countries (HICs). This competitive pressure is passed onto the producers – often small-scale and self-employed individuals and companies based in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Covid-19 – the impact on global garment chains and garment workers

In the global garment chains associated with the fast fashion industry suppliers in LMICs bear all the risk and responsibility: from sourcing materials and hiring workers to producing the final products. As the devastating Covid-19 pandemic has spread across the world, fashion brands that cater to markets in rich countries have cancelled billions of pounds worth of orders in Bangladesh alone. The impact is crushing, leaving over a million garment workers in Bangladesh with no income for the foreseeable future. This is compounded by the fact that workers in Bangladesh cannot rely on the safety nets – furlough schemes, bailouts, increased welfare payments – that have been rolled out in richer countries, benefiting both workers and businesses.

Covid-19 – African food supply chains and avoiding a potential hunger crisis

In a similar way, resources to bail out businesses and make social security payments to workers in food supply chains in Africa are limited. Partial or full shutdowns have adversely affected the livelihoods of millions of Africans who operate in formal and informal food related businesses. Based on a survey in seven African countries, The Economist recently reported that under a third of food processors were operating at full capacity, due to shortages of raw materials and social distancing rules. Food wholesalers and retailers are affected for the same reasons, with some traders creating artificial scarcity by stockpiling products, and then hiking prices.

The bulk of food producers in Africa are smallholder family farms. As the pandemic unfolds, planting could be affected by lack of access to fertiliser and seeds. Even more worryingly, problems could arise when farmers take their produce to the open markets in small African towns. Maintaining social distancing is difficult and the habitual use of cash is problematic. Consumers are suffering too. As The Economist reported, many are already affected by Covid-19, including millions of African children dependent on school meals.

Africa is a net food importer and nearly a quarter of its population is dependent on food aid. As the pandemic spreads, some food exporting countries are restricting exports, and food imports are also bound to drop due to shortfalls in foreign exchange and logistical difficulties such as border closures. Africans are already the most undernourished people in the world, and malnutrition is known to cause more ill health than any other cause. Without action to address these shortcomings in food supply chains, both in the short and longer term, populations risk even more widespread hunger and susceptibility to contracting the coronavirus.

Making value chain participation inclusive, equitable and sustainable

While Covid-19 has challenged and disrupted supply chains exposing the inherent unfairness and weaknesses within them, it also offers an opportunity to rethink and rebuild in a better way. In the short term this means, for example, governments and donors acting to mitigate the impacts of the loss of incomes. In the garment sector in Bangladesh, this could take the form of enhanced social protection measures. In African countries small scale irrigation could be expanded to compensate for the shortfall in food imports, along with investment in expanding marketplaces, thereby enabling physical distancing. In the longer-term citizens, governments, academic institutions, civil society, governments and businesses must work together to create an economic system that works for everyone.

Reviewing and refreshing global value chain governance is critical. South-south trade (including regional trade) and public-private-producer partnerships can help ensure that low- and middle-income countries capture their fair share from their participation in global value chains, offering positive ways forward. Value chain development must also aim at enhancing the innovation capacity of marginalised actors. This strategy has allowed Asian economies – such as Taiwan, South Korea and more recently China – to benefit from participation in global value chains by building domestic capacity in innovation and learning. The governance of value chains must be more inclusive and sustainable so that they serve all the producers and workers who constitute them: through fair wages, dignified working conditions, and equal opportunities.

This blog post is part of a series to introduce the Business, Markets and the State (BMAS) research cluster’s Position Papers. Read the position paper on food markets here and all the position papers here.

This blog is part of our blog series ‘Voices on Inclusive Trade’. Other blogs in this series:

- Can inclusive trade policy tackle multiple global challenges?

- Pathway to UK-India Free Trade Agreement: call for focused advocacy

- The future of UK-India trade and development – part one

- The future of UK-India trade and development – part two

- Trade, human rights and EU-India negotiations

- Can the RCEP strengthen global cooperation for trade, investment and sustainable development?

- Two developments for South-South trade and investments post Covid-19

- A new WTO chief creates opportunity to realise a globally inclusive trading system

- Amid shifting global trade dependencies, can the South provide greater certainty?

- Designing for Impact: South-South Trade and Investment

For more on inclusive trade and development, Watch our Inclusive Trade event series.