An elderly woman living in a low-income neighbourhood located along one of Karachi’s key drainage channels died when the roof of her house collapsed in July 2022. A landslide triggered by unprecedented monsoon rainfall was initially blamed. But her house was partially demolished in 2021 when a state-led eviction drive displaced 60,000 people for the upgradation of the city’s main drainage channels. Pakistan’s National Disaster Mitigation Authority backed the evictions, which were justified to mitigate the risk of urban flooding.

The tragic story of her death exposes the intensifying relationship between urban infrastructure, climate change and the interacting crises manifesting in cities. These are particularly severe in the informal city-settlements in Africa and South Asia, the fastest urbanising regions in the world.

The Covid-19 pandemic and migration intensified by climate, along with everyday risks such as infrastructural, evictions, racialised, ethnic and gendered violence, interact with the risks of urban flooding and extreme heat. These risks put the bodies, livelihoods, health, and safety of people living in poverty at a greater risk. The complex interactions between these risks are overlooked in research and policy.

Our project in Nairobi and Karachi surfaces four dimensions often missing from the analysis of interacting crises, and which emerge from understanding the complexity of risks and vulnerabilities in urban contexts: 1) the role of heat as an invisible risk, 2) the impacts on particular populations, 3) the embodiment of risk, and 4) temporal cycles of risk interaction.

In this blog, we explore what these four dimensions mean to those living in the rapidly growing informal settlements of Nairobi and Karachi.

-

The role of heat as an invisible risk

Extreme heat across South Asia and Africa has become more frequent and is lasting longer with more hot days and nights. Heat is a stealth killer: it doesn’t destroy homes or rip up trees, but it is deadly.

Heat interacts in multiple ways with urban spaces, infrastructure and populations. In Nairobi’s Kibera settlement, weak housing structures worsen the effects of both heat and cold. In Karachi, at the height of Covid-19 and summer heat, when people were stuck indoors, locals reported it was hotter indoors than outside. In communities that are vulnerable, women cannot go beyond settlement boundaries to find cooler sites because of insecurity and childcare responsibilities. These multiple risks compound women’s vulnerability.

2. The impacts on particular populations

Gender, ethnicity and class identities have been long understood as drivers of social vulnerability to climate change. The way interaction between urban infrastructure, climate change and other risks play out through such social divisions is often invisible.

For example, in Nairobi, the construction of a new link road triggered demolitions and forced evictions in Kibera, saw the water supply cut off, the destruction of schools, increased exposure to pollutants, risk of accidents, and exacerbated flooding during and after construction. During this, women and girls had to fetch water from far away sources and go to schools further afield. This exposed them to crime and other insecurities.

Similarly in Karachi, low-income neighbourhoods such as the Kausar Niazi Colony have faced the brunt of violent evictions in conjunction with catastrophic flooding. The destruction of washrooms and shelters has more devastating effects on women’s dignity and health, so they are often a priority to be rebuilt to offer some sort of protection.

3. Embodiment of risk interaction

Our research from Karachi shows that exposure to these risks greatly impacts physical distress that leads to and worsens anxiety and psychological stress, creating cycles of compounding risks that are often overlooked. One woman described herself as living with mental trauma “every day” after a flood, where her husband lost a limb and she experienced gender-based violence.

4. Temporal cycles of risk interaction

The influence of time is little explored in risk research and practice. In Karachi, physical risks, especially those that are heat and eviction related, are higher during the day due to extreme heat and humidity. However, safety-related risks and perceived vulnerability are much higher at night time. In Kibera, residents reported the risks of flooding during the night compared to during the day compounded and worsened. During the night they face greater insecurity, and the loss of property due to flooding in increased, as one resident reported,

“At night you don’t know where you can run to, where you can get help, you can’t move because of the security issues”.

Infrastructures of repair

While people living in these urban areas point to a clear connection between problems with the existing and development of infrastructure, and unpredictable weather, they feel that governments and international organisations are failing to fulfil their responsibilities.

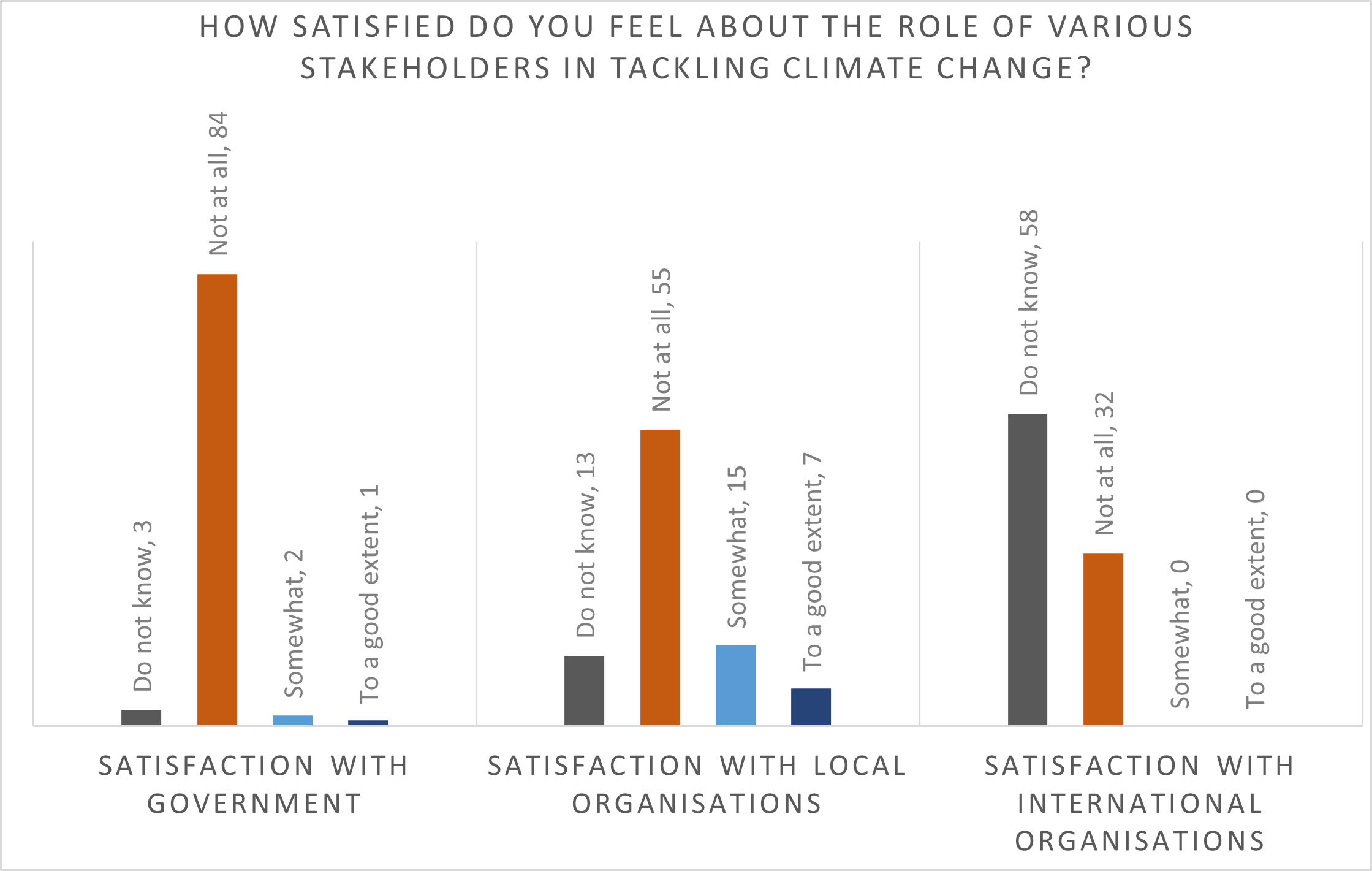

In a study we conducted for this project in July 2021 with two communities most vulnerable to climate change in Karachi, respondents shared strong dissatisfaction with how institutions were dealing with these threats (Figure 1). About 93% of people claimed they were completely dissatisfied with government interventions regarding climate change.

In response to such failures, residents are involved in repairing physical and social infrastructure and networks. But there is a need to understand how they enrol the labour of women in particular, and how they can demonstrate resource-efficient and decentralised methods of collaboration that link action and mediate complex risks.

We will be seeking to understand those approaches over the next two years. With a team of researchers and urban activists from the Institute of Development Studies, UK; Karachi Urban Lab, IBA, Karachi; Kounkuey Design Initiative, Kenya, the Open University UK, and the University of Oslo, our project will be working with residents of low-income neighbourhoods and communities in Karachi and Nairobi to uncover stories of climate repair and the implications for women’s bodies, livelihoods, health, and safety.

You can keep up-to-date with our work on Twitter by following @nbokhi_climate and on our project page.

We would like to acknowledge the contributions to this research by Safina Azeem, Bosibori Barake, Regina Opondo, Allan Ouko, Arsam Saleem, Duaa Sameer, and Amos Wandera