This is the fourth blog in our series on ‘Lessons on using Contribution analysis for Impact Evaluation’. This blog will describe how we used the concept of causal hotspots as a way to zoom in, unpack, and make the hard choices about where producing evidence brings the most value to build an understanding of how the intervention works.

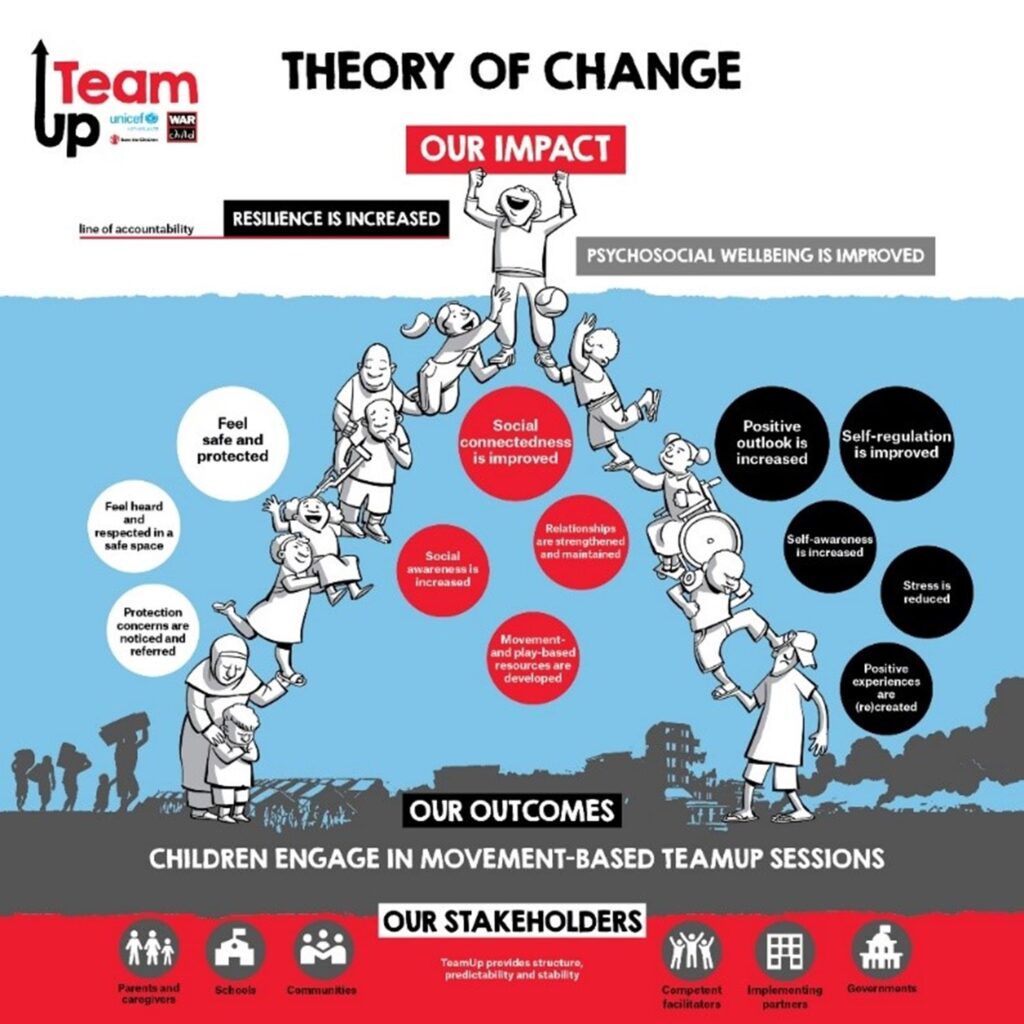

The evaluation described was commissioned by Save the Children The Netherlands, which wanted to evaluate a play and movement-based psychosocial wellbeing intervention (TeamUp) for children and young people (aged 6 to 18 years old) in asylum reception centres. The main evaluation question was: “How, why, and under which circumstances does TeamUp contribute to promoting the psychosocial wellbeing of children in Dutch asylum reception centers?” The commissioner’s interest was to build an understanding of how and why TeamUp contributes to psychosocial wellbeing in different contexts, and when it does not, explore the theory of change (Figure 1). The commissioner (TeamUp MEAL lead – Tom) was an alumnus of our contribution analysis for impact evaluation and participatory monitoring and evaluation short courses. Thus we started from a common understanding of theory-based and participatory evaluation approaches. We undertook this impact evaluation collaboratively between IDS and the TeamUp team within Save the Children, to maximize relevance and feasibility from the program team on the one hand, and independence and expertise from IDS on the other.

Identifying causal hotspots in collaboration with the programme team

Given that the causal pathways towards improved psychosocial wellbeing for refugee children are long and unpredictable, we employed a causal hotspots strategy to focus on where there were: 1) gaps in evidence to support the causal connections and 2) strong interest and curiosity from the TeamUp team to learn more about their impact. Identifying the causal hotspots was done through an iterative process with the TeamUp programme team (including programme developers, team leader and regional coordinators who look after the training and mentoring of volunteers) and MEAL team.

Specifying outcomes

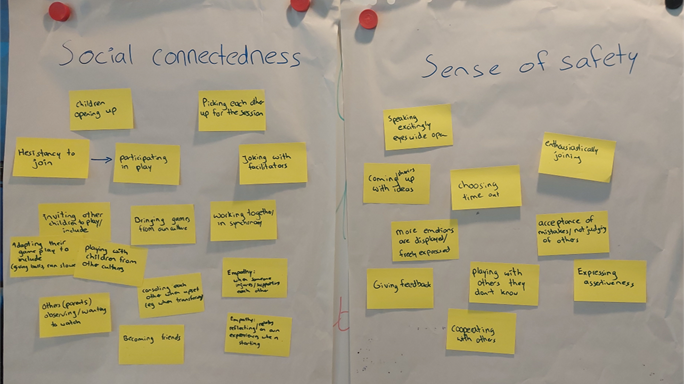

During a series of workshops we collectively detailed the causal pathways starting from the existing TeamUp Theory of Change and its evidence base. This first involved specifying the outcomes and describing what these outcomes look like when they present themselves in the children, based on the experiential knowledge of the facilitation team and existing MEAL data (Fig 2).

Initial exploration and visualization of causal pathways

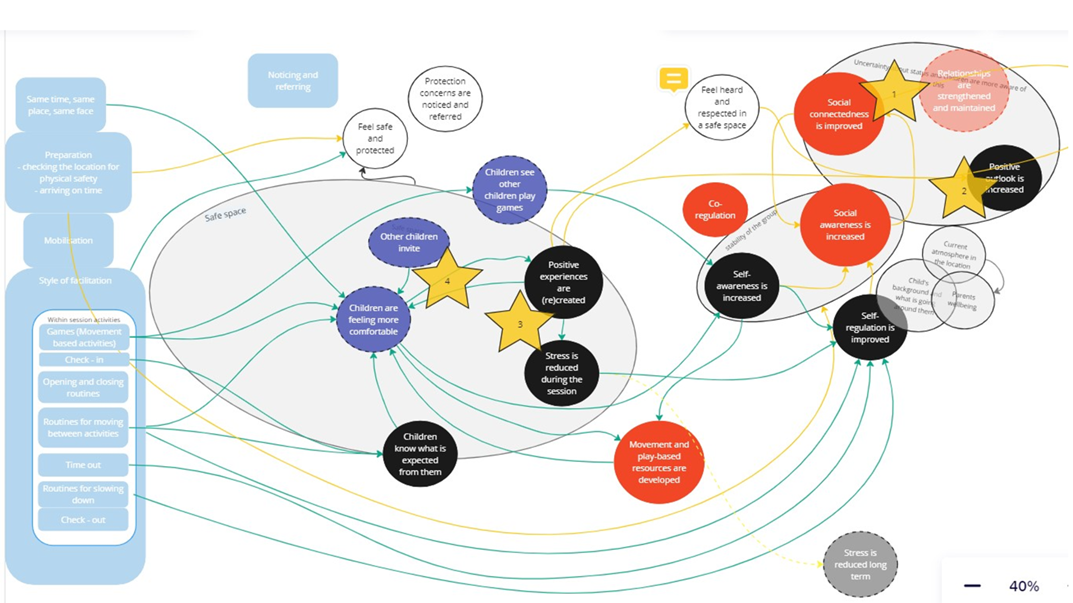

We needed to detail the causal pathways from the intervention to the outcomes to help build a ‘useful Theory of Change’ and identify causal hotspots where empirical work would provide the most value. For this exercise we selected four different locations and age groups, to get a better understanding of whether the team hypothesized the same outcomes to take place in the same logical sequencing in different contexts. It also helped us to build a picture of what contextual factors might shape how the intervention contributes to the outcomes (in line with our realist contribution analysis). Building on the experiential knowledge of regional coordinators, the exercise allowed us to sequence the outcomes and identify assumptions about how they link to the elements of the TeamUp intervention as well as to explore initial hypotheses about the key contextual factors that play a role. During the session, we visualised the causal pathways on a Miro board (Fig 3):

Identification of causal hotspots

We decided on three causal hotspots based on where the evidence base was the weakest and where the team was particularly interested to learn from this evaluation. For each hotspot, we wrote the narrative of the causal pathways, explored the literature and identified evidence from previous TeamUp evaluations to fill gaps and identify any remaining gaps.

Theorising causal hotspots and identifying appropriate evaluation methods

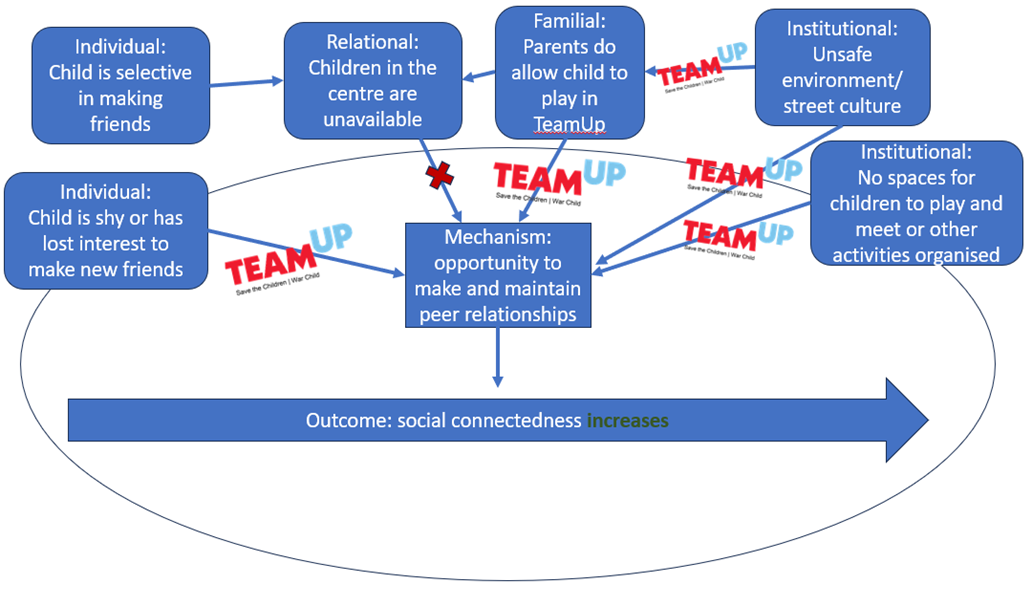

We finalised the inception phase by detailing the realist programme theories for each hotspot and the underlying assumptions within them. These descriptions formed the basis of primary data collection. The causal hotspots each had their own sub-evaluation question and specific data collection methods, forming the overall impact evaluation design (Fig 4):

Seeing the intervention within the system

The hotspot related to social connectedness was about a more distant outcome within the theory of change and we therefore applied a system’s lens. Given the complexity of the asylum reception centre context that TeamUp is implemented in, we looked at TeamUp’s contribution to this outcome as one amongst many system factors that influence children’s experiences of social connectedness in asylum reception centres. By decentring the intervention in our question, we aimed to develop a deeper understanding of the system within which the TeamUp intervention is implemented and how it does (or not) contribute to the outcome alongside other contextual factors.

We used a bricolage of participatory narrative methods, combining elements of life stories, most significant change and outcome harvesting as these provided rich information about the contextual factors that contribute to experiences of social connectedness of children in asylum centres. factors that contribute to experiences of social connectedness of children in asylum centres.

- With children, we used a story collection approach with open ended prompts about who they mostly connect with and how they build social connections in the asylum centre.

- With parents, we used an adapted most significant change approach, with added questions that provided us with causal information about what contributed to the changes they mentioned (based on outcome harvesting).

We did not directly prompt participants to talk about the intervention, but they did still provide detailed information about how they experienced the role of TeamUp within the system of asylum reception centres. This allowed us to create a detailed picture of where TeamUp contributed opportunities for children to make and maintain friendships (Figure 5, for example, where the centre is experienced as an unsafe environment and parents do not allow their children to play outside, they do send them to TeamUp, which is perceived to be safe, which then provides children with the opportunity to make and maintain peer relationships, resulting in an increase in social connectedness). This detailed picture was useful for the TeamUp team to understand that their contribution to social connectedness is strongest in locations with a lot of new children, locations that are relatively unsafe, and for children who are more socially withdrawn. This provides helpful insights into how to focus their attention.

Final reflections

Using causal hotspots allowed us to gather evidence for specific parts of the theory of change to build an understanding of how TeamUp contributes to psychosocial wellbeing in different contexts, and when it does not. Given the interrelated nature of the outcomes in the theory of change, the rich data from this evaluation also provided valuable insights into other outcomes. This highlights the importance of aspiring to an iterative and accumulative approach to knowledge building about interventions where we keep updating and refining our theories of change based on new evidence from our monitoring, evaluation, learning and research endeavours.

Learn how to design impact evaluations more effectively with “Contribution Analysis for Impact Evaluation” course convened by Giel Ton, Marina Apgar and Mieke Snijder. This course equips you with the tools to enhance impact evaluations by navigating complexities in development programs. Explore a structured approach to refining Theory of Change iteratively, alongside mixed-method research designs and innovative techniques like Qualitative Comparative Analysis and Realist Evaluation.