Part 1. Key Qualities of Research-Policy Partnerships

“The Impact Initiative has really helped explore some of the practical opportunities and approaches for research policy partnerships to make a stronger contribution to development policy and practice. This has important implications for UK funded researchers seeking lasting and beneficial impacts for developing countries.”

Mark Claydon Smith, Deputy Director of International Development, UK Research Innovation (UKRI)

1.1 Background

Globally, increasing attention is being given to developing cutting-edge research in collaboration with those most likely to use or benefit from it. In July 2019, the Department for International Development (DFID), Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), UK Research Innovation, UK Collaborative on Development Research and the Impact Initiative jointly convened a knowledge-exchange event in London. The event built on IDS Bulletin 50.1 ‘Exploring Research–Policy Partnerships in International Development’, prepared by the Impact Initiative. It brought together a diverse group of more than 20 ESRC-DFID-funded researchers and practitioners from five countries, working on education, disability rights, child poverty, conflict and health reform, inviting them to reflect on their experiences of partnership for development that spanned research, policy and practice. Their case studies and a literature review of development partnership theory was the basis for a set of three inter-related partnership qualities. The case studies and commentaries below are featured in the above-mentioned IDS Bulletin.

“The ESRC-DFID Strategic Partnership has been successful in demonstrating what approaches [to partnership] are effective, being sharply focused on the combination of relevance and academic rigour with targeted, well-planned research uptake methods.”

Diana Dalton, Former Deputy Director of DFID’s Research Evidence Division (Excerpt from the Foreword in IDS Bulletin 50.1)

1.2 Defining partnerships for policy change in development

Analysis of partnerships for international development has tended to focus on interactions between donors in the global North and national partners in Southern contexts, whether government, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or research institutions. This is a crucial field of study, particularly as the movement to ‘decolonise development’ gains momentum. However, our focus was specifically on partnerships between research producers and users in international development settings, given this is an area that has received more limited attention. A framework for such partnerships aimed at achieving impact must consider the dynamics of real-world policy engagement. Useful here are concepts of mutual interdependence that maximise benefits for all. This means mutual commitment to the objectives of the collaboration and a strategy that is compatible with each actor’s mission, values and goals.

1.3 How do inter-sector partnerships maximise impact?

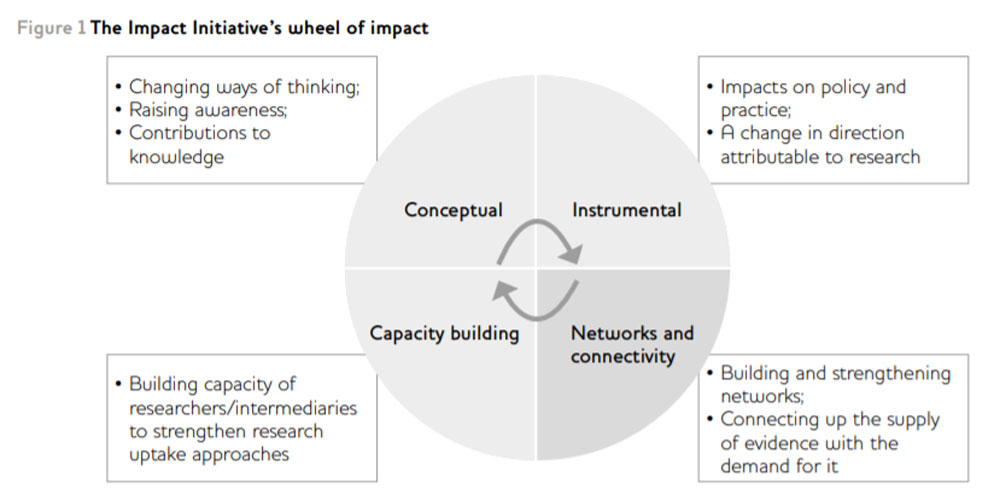

Various perspectives on how research influences policy and practice affect our understanding of the value and ideal design of research–policy partnerships. Concepts range from traditional linear relationships between new knowledge and policy innovation derived from the natural sciences; to complex interactive models intertwining science and society. Donors and researchers have largely settled on 3–4 core definitions or modes of impact. These definitions are useful when thinking about the impact of effective research–policy partnerships beyond academia.

Source: Georgalakis and Rose (2019: 2)

1.4 Is partnership between specialists enough?

Connections between research producers and users, and productive relationships between key individuals and institutions are important, but on their own are inadequate. Policymakers operate in environments full of uncertainty, making decisions based on ambiguous information. Advocates of evidenced-informed policy need to simplify complex problems and frame information to meet policymakers’ demands.

1.5 What are the key qualities of effective research–policy partnerships?

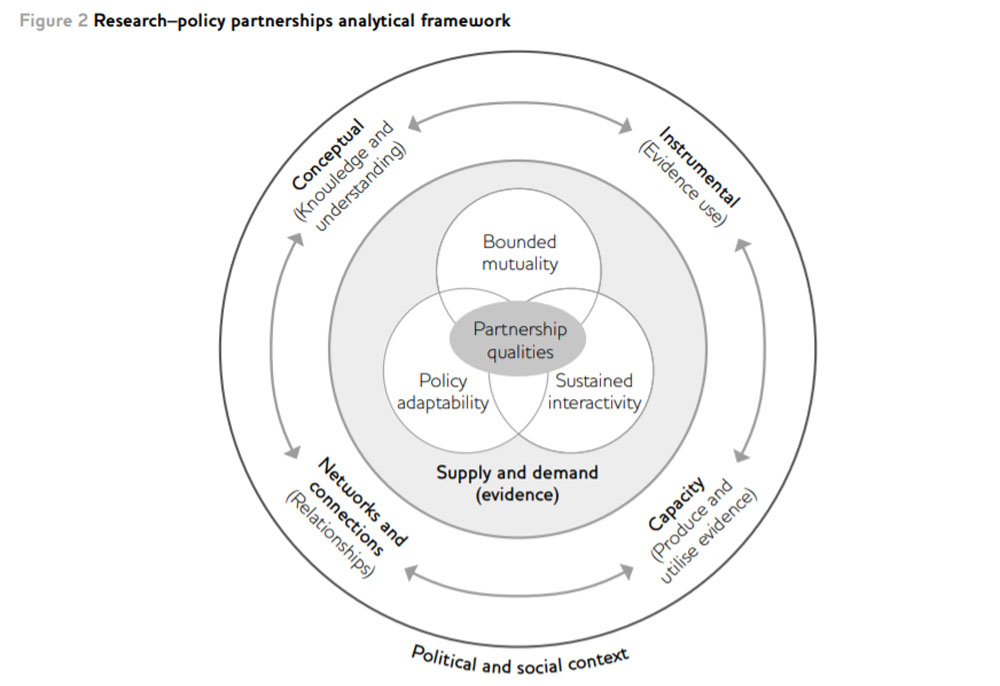

We have identified three inter-related qualities of effective partnerships, testing them with donors, researchers, and civil society and government partners.

Source: Georgalakis and Rose (2019: 10)

Bounded mutuality

Key to successful partnerships is a common understanding of a given problem, and compatible values which underpin collaboration even if partners have different mandates. In research–policy partnerships, this occurs where evidence supply and demand converge. For example, a shared agenda for improving education or health systems may cement relations between policy advisors, who must deliver viable recommendations to decision makers, and practitioners and researchers hoping to inform programme design.

Nonetheless, partnerships are bounded by differences in organisational cultures, priorities and accountability. Partners seek to recognise these differences, sometimes compromising and playing to one another’s strengths. This pragmatic approach need not undermine core values. There are risks, but acknowledging that partners have different objectives and interests can be liberating, providing opportunities for learning and greater leverage.

Source: Mulugeta et al. (2019: 112, 99–120)

Sustained interactivity

Sustained means building engagement from the outset of the research process and beyond. The most successful research partnerships continue after projects have ended. Partners see value in working together and look for opportunities for longer-term collaboration. Attempts at sustained interactivity may be politically charged. As well as formal structures, such as advisory groups, more iterative and evolving approaches to partnership are essential to building trust.

This approach recognises that research-policy processes are relational and messy, not technical or ordered. The conventional language of supply of evidence by researchers and demand for this evidence by policy actors masks the blurring of boundaries between research producers and users, and how learning and influence go both ways. Traditional policy cycle concepts have been discredited, and social and relational models of research engagement require ongoing interaction among a fluctuating group of partners and boundary partners outside the core partnership.

Source: Yeates, Moeti and Luwabelwa (2019: 131, 121–142)

Policy adaptability

Adaptability refers to how partnerships identify key influencing spaces and re-frame evidence for specific audiences, adapting to changes in political or social contexts. Diversity among the active members of the partnership informs engagement strategies and even the research process itself, tailoring it to particular contexts. Collaboration with boundary partners, such as policy advocates, or other brokers, such as the media, is essential because they may incorporate evidence into their own campaigns and priorities. Intermediaries expand partnerships’ reach and legitimacy. The ability of research collaborations to provide coherent responses to perceived policy dilemmas resides in more than just the rigour of their research and the inclusivity of their partnership.

Using donors, implementation agencies and policy actors as brokers allows access to otherwise closed policy spaces. Adaptability is not just about fast and furious engagement in live policy processes. It is also necessary for longer-term agenda setting, which may mean deviating from envisaged pathways as new information affects how evidence is understood and used.

Source: Hinton, Bronwin and Savage (2019: 43–64)

“Education researchers understand policy and policymakers have got their heads around research”

Richard Clarke, DFID’s Director General for Policy, Research and Humanitarian

Part 2. Making research-policy partnerships work: Funders’ and researchers recommendations

At the partnerships framework launch, a diverse group of donors, ESRC-DFID-funded researchers, policy partners and civil society organisations discussed how to use and improve the framework, and its implications for their work. Their conclusions are summarised below.

2.1 Deploy the framework at the design stage of a research process to increase partnership viability

The inception phase of a research programme often entails stakeholder mapping and political economy analysis. The three qualities described above could be used to explore how the partnership relates to wider contextual analysis. Research partnerships are as much a product of social and political norms as the research area being addressed. An inclusive and participatory approach builds trust and mutual understanding around:

- Exploiting differences in expertise and networks.

- Clarifying roles and responsibilities.

- Developing processes to continually exchange ideas.

- Sustaining longer-term relations.

- Framing evidence for policy audiences.

- Identifying boundary partners.

Participants at the launch event agreed that research partnerships can be closely associated with co-production of research. In some cases participatory methodologies are relevant depending on the research objectives and approach. Meaningful engagement with partners may be viewed as an end in itself, empowering those who often lack a voice in international research studies and achieving ‘cognitive justice’. From this perspective, research is development, not for development. Partnership is a democratic tool that promotes equity and inclusivity.

Other valid and epistemically robust approaches to research also exist, including ones that envision a clearer division of labour between different partners in the pathways to impact process and a valid role for ‘independent research’. Such approaches still recognise the importance of engaging with policy actors throughout the research process including, for example, to frame relevant research questions, ensure appropriate interpretation of the data, and promote dissemination of the findings.

“If the question isn’t being asked in the right way, it’s unlikely to be impactful. We often think of the research as the key to impact, but it’s actually as much about whether anyone is asking the right question.”

Mike Aaronson, Chair, Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF)

2.2 Be honest about power dynamics and build trust

Donors and researchers with whom we shared the framework (presented above) agreed with the general view that equitable partnerships are desirable and morally imperative but, as the framework suggests, are not always a necessary pre-condition for innovative research and societal relevance. Tensions, trade-offs and compromises that occur when research and policy come together may still lead to progressive change. Trust is important, though, and some researchers urged caution in partnering with policy actors. Despite converging agendas, each partner is governed by a separate mandate. Other participants mentioned the importance of not underestimating researchers’ power. Government ministers might fear what research says and challenging dominant policy narratives can place enormous pressure on partnerships, so researchers need to be mindful of this in the presentation of their evidence.

“Knowledge is always partial and even rigorous social science is always contestable. It takes long term partnerships and mutual respect to reduce the risk that evidence will be thrown out for being perceived as irrelevant or not useful.”

Melissa Leach, Director, Institute of Development Studies

“There are undoubtedly tensions between conducting rigorous research that can take 5-10 years, and the change in policy direction brought on by often much shorter political cycles.”

Diana Dalton, Former Deputy Director of the Research and Evidence Division, DFID (Excerpt from the Foreword in IDS Bulletin 50.1)

“Evidence is political and who produces that evidence is political… How do you build from sustained interactivity to systemic change in how evidence is produced and engaged with?”

Kate Newman, Head of Research, Evidence and Learning, Christian Aid

“In Kenya – too often, researchers want to mobilise persons with disabilities so they can collect information but without any plans for their further involvement in the research or dissemination.”

Anderson Gitonga Kiraithev, United Disabled Persons of Kenya

2.3 Identify boundary partners and work with brokers

The movement to work across scientific disciplines and sectors acknowledges that tackling global challenges requires new forms of research–policy partnership. In global health, for example, there have been attempts to overcome barriers between researchers and policymakers by building multidisciplinary teams of academics, practitioners and government officials.

Although close relations between research and policy actors may be key to success, participants also discussed the importance of relationships with boundary partners and research intermediaries, such as the media, NGOs and civil society. These boundary partners can be mobilised at key moments and may be in a position to engage with audiences beyond the core partners’ reach. Their perceived legitimacy and ability to frame research in non-academic terms can raise awareness and build support for changes in policy direction.

Long-standing partnerships with policy actors who are often mid-level civil servants and advisors do not make it any less important to construct compelling policy-friendly narratives and identify key influencing opportunities in the political sphere. Also necessary are good timing, policy-relevant research, and the ability to contextualise research evidence for live policy issues and having individuals positioned appropriately. Mutual agendas and close working relationships do not automatically generate these qualities and thus deserve special attention.

“In our case, it was us the practitioners that went to the policymakers in a changing political context where research was just beginning to be engaged in democratic conversations. If the doors are closed, we have to use the windows to get into their offices. We managed to convince the Ministry of Women, Children and Youth to convene a meeting to engage the researchers and young people with the policymakers.”

Anannia Admassu, Director, CHADET

2.4 Health-checking existing collaborations

Partnerships change over time: much is taken for granted or not discussed; initial strategies may not be revisited; partners may have very different perspectives on the partnership. Using the framework as part of project learning and adaptation, it is possible to explore these issues non-judgementally, to rekindle initial enthusiasm and optimise partnerships.

“We all have different power, so then the question is how we use our power in the most effective ways”

Charlotte Watts, DFID Chief Scientific Advisor

“Timing is important, implementation is time bound. But we must not forget the issue of poor research, not all research is excellent. Recommendations are often not feasible, not based upon the real situation, or they can be far too general.’

Mushtaque Chowdhury, Vice Chair, BRAC

2.5 Enable mutuality, interactivity and adaptability

Research collaborations are a product of pre-existing relationships and power dynamics, shaped by theories of change, perceived mutual benefits, and a competitive funding environment in which there is a rush to secure solid partners deemed to be a good fit. The framework has implications for design and assessment of research calls. Support for interdisciplinarity is already strong, but more could be done to bring together ‘odd bedfellows’ who have little experience of working together or encourage prospective partners to bridge different networks and spheres of influence. Sustained interactivity requires support for iterative planning and ongoing communication; policy adaptability needs flexibility in planning and resourcing activities – this is as much about procurement as research strategy.

“Procurement departments in donor organisations need to take a good hard look at this partnerships framework. It has important lessons for how contracts are set up and managed”

Louise Shaxson, Director of Digital Societies – ODI

“We’ve talked a lot about the politics of policy today, but not of the politics of research funding – this plays a big role in framing research partnerships… There is a danger to focusing on partnerships as bounded entities, rather than seeing research collaboration as part of a more complex knowledge ecosystem. If we want to make practice more equitable, we need to examine participation and make changes across the system.”

Jude Fransman, Open University

Part 3. Conclusions

The framework for research–policy partnerships presented here is shaped by an understanding of evidence-into-policy processes as fundamentally social and interactive, underpinned by political context, social norms and power. All three partnership qualities: Bounded Mutuality, Sustained Interactivity and Policy Adaptability, are found in the case studies from the ESRC/DFID-funded research. Although there is evidence that these qualities have brought about desired changes in terms of evidence use, capacity, knowledge and relationships, the comparative strength of the qualities in specific partnerships also suggests that even more could be achieved if they were more deeply rooted.

We propose that using this framework at the research design stage could increase partnerships’ viability by taking into account the importance of mutuality, interactivity and policy adaptability from the outset. We hope others will seek to validate this concept with existing methodologies and literature, and apply variations of it to their own work.

To find out more about the framework and how to use it in your own work, go to IDS Bulletin 50.1: ‘Exploring Research–Policy Partnerships in International Development’

Further reading

Baker, A; Crossman, S; Mitchell, I.; Tyskerud, Y and Warwick, R. (2018) How the UK Spends its Aid Budget, London,

Dalton, D. (2019a), ‘Foreword’, IDS Bulletin 50.1: ix

Georgalakis, G. and Rose, P. (2019) ‘Exploring Research–Policy Partnerships in International Development’ IDS Bulletin 50.1

Hinton, R.; Bronwin, R. and Savage, L. (2019) ‘Pathways to Impact: Insights from Research Partnerships in Uganda and India’, IDS Bulletin 50.1: 43–64

Mulugeta, M.F.; Gebresenbet, F.; Tariku, Y. and Nettir, E. (2019) ‘Fundamental Challenges in Academic–Government Partnership in Conflict Research in the Pastoral Lowlands of Ethiopia’, IDS Bulletin 50.1: 99–120

UK Government (2018) The Allocation of Funding for Research and Innovation, London: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

Yeates, N.; Moeti, T. and Luwabelwa, M. (2019) ‘Regional Research–Policy Partnerships for Health Equity and Inclusive Development: Reflections on Opportunities and Challenges from a Southern African Perspective’, IDS Bulletin 50.1: 121–142